Roma (Alfonso Cuarón, 2018) – Global Acquisition – Art Cinema

Reported Budget: $15 million – Reported Netflix Price: $20 million

Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio) is the live-in maid of a middle-class family in Mexico City in 1970. Through her eyes we see two loosely structured stories unfold: that of the family for whom she works, and her own which involves an unplanned pregnancy and the challenges she faces caring for a family that loves her but also often takes her for granted. The family’s story is witnessed by Cleo only in fragments, á la the famous play Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead, but these fragments efficiently convey the fact that the family’s father (Fernando Grediaga) is abandoning the rest of the family, leaving the mother Sofía (Marina de Tavira), grandmother Teresa (Verónica García) and Cleo herself to take care of the children without any emotional or financial support.

While we may argue about whether filmgoers of all tastes will enjoy the film, there can be no denying that Roma is an artistic masterpiece. There is no element of style that writer-director-producer-cinematographer Alfonso Cuarón does not use well in telling a moving story that is both personal, but also universal, but also particular to its time and place. A review like this one could thus go on and on in rapturous detail about everything that was great, but I will focus on two aspects of the film here and leave it to viewers to check out the rest. The first of these is the creative use of space in the film and the second will be the acting, particularly the performance of Yalitza Aparicio which is rightly getting a great deal of attention.

When it comes to appreciating Cuarón’s mastery of style in the film, I will focus on three scenes in particular, all of which manipulate space in slightly different ways. These are a scene in which Teresa and Cleo go shopping for a crib while a demonstration turns into a massacre on the streets outside of the store, a later scene in which Cleo gives birth (spoilers here I am afraid, skip over if you want to be surprised) and a scene that is sure to become iconic, one in which is set on the beach when Cleo rescues two of the family’s children from drowning.

These three scenes are united by their ability to present multiple planes of action, mostly offscreen, except the delivery scene which pointedly presents both planes of action simultaneously. In the shopping scene, offscreen sound is used masterfully to generate tonal contrasts between the bourgeois shopping taking place onscreen and the growing chaos offscreen, while also continuing the film’s bigger strategy of using sound to develop a bigger world surrounding the characters. (For this reason, it is arguably superior audio equipment rather than the bigger screens that would make a theatrical experience richer than watching Roma at home.) The proximity of the offscreen sound also generates tension that culminates with the rioters bursting into the store.

The beach scene on the other hand uses offscreen sound in a slightly different way, but also generates a great deal of tension. In a single take, we see Cleo walk away from the water and turn her back on the children swimming. Her furtive glances over her shoulder as she walks up the beach help to build suspense, but adding to that tension is the LACK of offscreen sound telling us what is happening to the children (we only hear the waves crashing). The camera also does not show us what is happening, but sound has a way of unsettling us more than image. In any case, we get neither and the results are excruciating as we (and Cleo) grow increasingly uncomfortable and worried. This scene has numerous stylistic echoes of previous scenes in which the kids run wild on the streets of Mexico City with Cleo frantically searching for them.

The delivery scene in contrast shows us everything in a single take, using deep focus as we see the baby brought over to a second table with Cleo in the foreground having to watch (as we do) the horrific sight of the doctors somewhat indifferently attempting to revive the infant. When they can’t it’s devastating, but even worse in some ways is that the scene continues with the doctors callously yanking the baby away from Cleo and carrying out medical protocols for handling dead children without shielding Cleo from the heartbreaking spectacle. Crucially, Cuarón doesn’t let the audience look away either.

At the heart of all of these scenes and the movie itself is Aparicio’s performance which is one of the great nonprofessional performances in film history, deserving a place alongside Lamberto Maggiorani’s Antonio in The Bicycle Thieves or Karuna Bannerjee in the first two parts of The Apu Trilogy. Like those performances, Aparicio seems to live her role and everything she does seems natural and unperformed. Her stoicism even in moments of outrageous injustice or cathartic relief and happiness keeps the film from veering into melodrama and moreover is true to life. Looking forward, one just hopes she gets more opportunities and perhaps some roles that give her the chance to show off a wider range of dramatic abilities beyond the somewhat minimalist performance given here. Unfortunately, most of the great nonprofessional performers in film history haven’t gotten these kind of chances.

Roma is thus a film that I think very highly of, but is it for everyone? I have given it five stars because I think it is accessible enough that all filmgoers will enjoy it. Yes there are some slow parts in terms of the narrative progression in the film, particularly at the opening, but these, to me at least, are not as challenging as similar narrative looseness in other art films I have reviewed for the blog (e.g. Happy as Lazzaro and Sunday’s Illness). And yes it is in black and white and the Spanish language, but no good filmgoer should be put off by these.

So what about Netflix? Do they deserve credit for this masterpiece and its global fame? Yes and no. We should remember that they did not, in fact, make this film or even take a chance on whether or not Cuarón could pull off this ambitious idea. They bought the film from Participant Media after it had already been made, or at least when it was close to being done with post-production, meaning they could see it was a masterpiece already. Participant deserves the credit for gambling $15 million – an unheard of sum in Latin American cinema – on this personal, Mexican story.

But Netflix’s involvement as a distributor cannot be underestimated. Not only is the film widely and immediately available to many people who will invariably see it whereas they wouldn’t have with a normal theatrical release, but Netflix’s ability to generate controversy was perhaps even more important in raising the film’s profile. The film has become the focal point of numerous controversies surrounding the company’s relationship to the institutions of “legit” cinema – such as film festivals (remember Cannes turned it down whereas Venice embraced it), the Oscars and theaters themselves. Put simply, more people know about Roma because of these controversies. Given its universal resonance and masterful film-making, this may be something to lament, if only because it should be universally known for those qualities and not for a standoff between different factions in the film industry. But then, the more that see this film the better, as it will go down as one of the best films in recent memory.

Netflix Tendencies

Notable Corporate Alliances

Besides financing and selling this film, Participant Media also financed the upcoming film The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind and developed the series Central Park Five, both of which will be Netflix originals. The company also sold Beasts of No Nation to Netflix, which became the first Netflix “original” fiction film in 2015, as well as The Square, an important documentary feature for the service.

Underrepresented Groups/Difficult Themes

While Cuarón is hardly without resources or connections – there were six Hollywood companies supposedly interested in distributing the film – this is still an instance of challenging subject matter being given a big platform by Netflix. A poor, dark-skinned indigenous Mexican maid is not a prototypical movie heroine and it is thus brave for Participant/Cuarón and Netflix to put her at the center of the story, particularly with the tragic things that occur in the film.

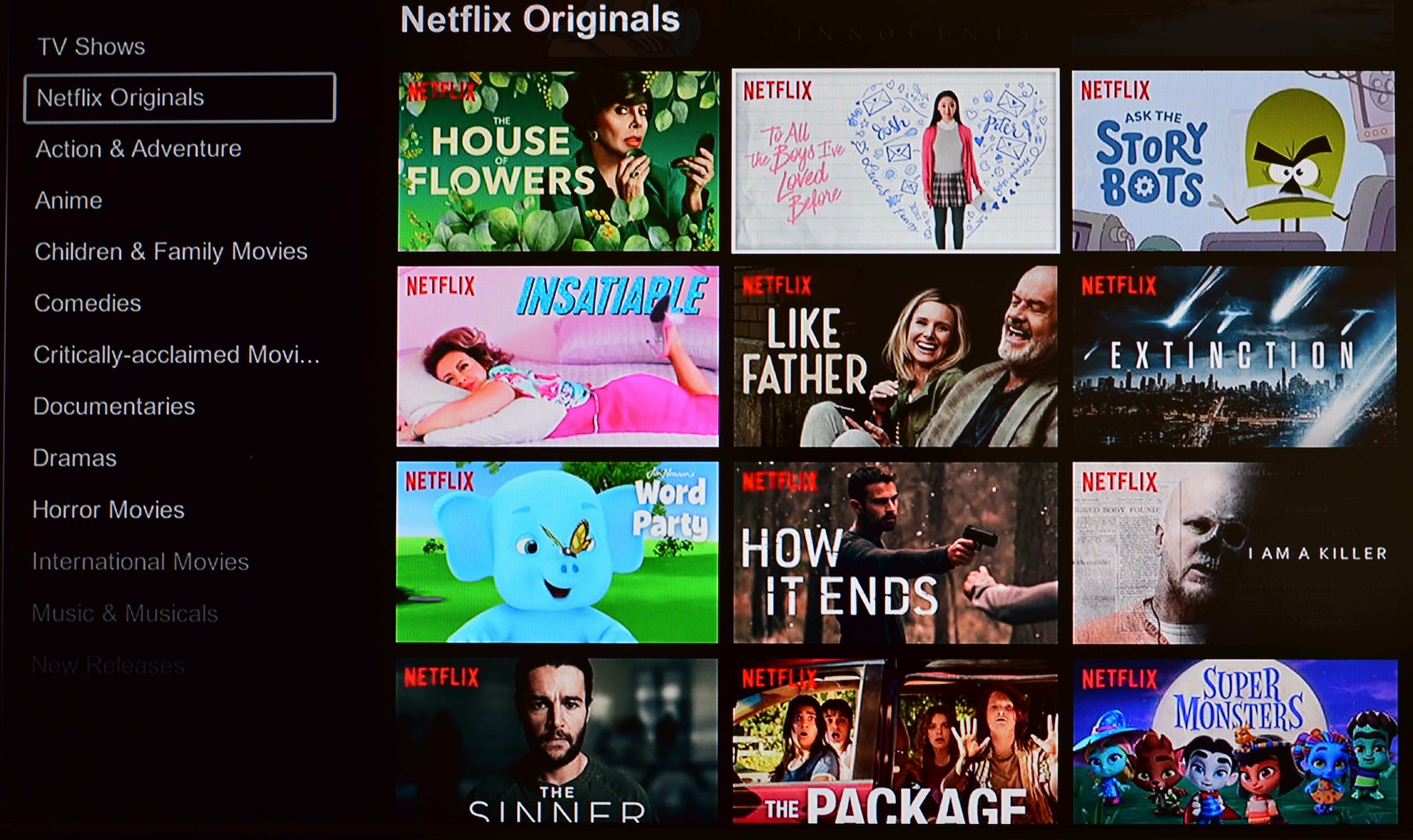

[…] of feel good hits like To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before and the critical accolades that greeted Roma, Bright feels very dated and one wonders why exactly Netflix wants to keep it going now that it has […]

LikeLike

[…] that the service has made to date. Moreover, along with the critical accolades that have greeted Roma, the popular success of this film has helped to make December 2018 the month in which Netflix films […]

LikeLike

[…] have gained a great deal of artistic “cred” in 2018. The reasons for this revolve mainly around Roma, a film it won in an auction and didn’t actually produce, but most consumers (and […]

LikeLike

[…] Netflix’s originals such as Zoya Akhtar’s section of Lust Stories or even the venerable Roma. […]

LikeLike

[…] still dealing with in many ways. In this sense, Mudbound foreshadows the controversies surrounding Roma in 2018/2019 with Cuarón’s film likewise benefiting greatly in terms of exposure caused as much […]

LikeLike

[…] in the fall of 2018. This will forever be remembered for Netflix’s Oscar pushes for Roma, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, Private Life and others, not to mention the promotional spending on […]

LikeLike

[…] a long way to go before we can say that they are being represented enough. As was the case with Roma, we can say that Netflix is legitimately helping this cause by buying these films up for […]

LikeLike

[…] have been involved in one way or another in a number of Netflix original films, including Roma, Beasts of No Nation, The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind as well as The Square, a documentary which was […]

LikeLike

[…] same impulse to seem like the guardians of Cinema with a capital C guided Netflix’s purchase of Roma and its re-editing of The Other Side of the Wind, both of which defied conventional commercial […]

LikeLike

[…] accelerate quickly. This year, even more than the last when Netflix spent a fortune campaigning for Roma, all eyes will be on the streaming service. Its lead contenders for Best Picture are said to be The […]

LikeLike

[…] non-English language original film was…Airplane Mode, a heretofore obscure Brazilian comedy. Not Roma or any of the many Spanish-language titles; not Lust Stories or any of the films directed at the […]

LikeLike

[…] performances in recent memory and truly on par with Yalitza Aparicio’s now legendary turn in Roma. As was the case with Aparicio vis-a-vis Cleo, Kayama’s life bears a great deal of resemblance to […]

LikeLike